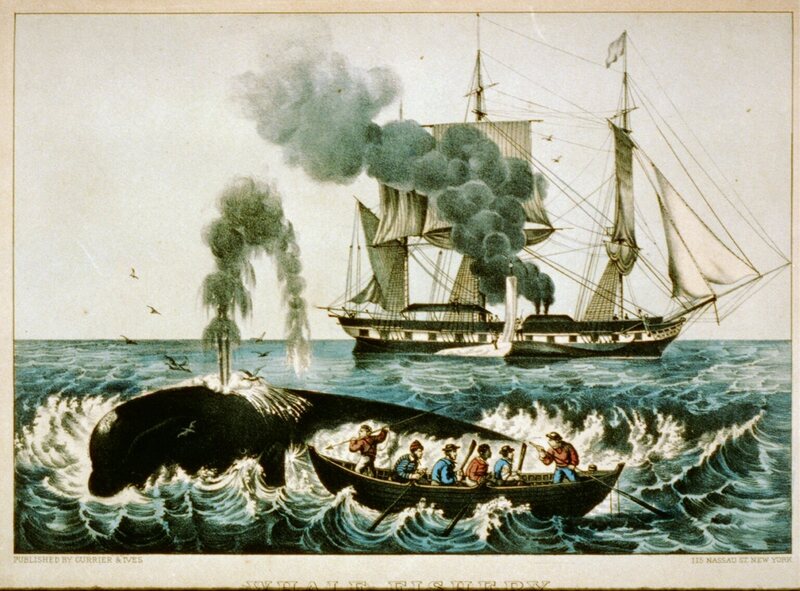

Whalers wrote about woggins all the time.

On December 20, 1792, the whaling ship Asia

was making its way through the Desolation Islands, in the Indian Ocean,

when the crew decided to stop for lunch. According to the log keeper,

the meal was a great success: “At 1 PM Sent our Boat on Shore After Some

refreshments,” he wrote. “She returned with A Plenty of Woggins we

Cooked Some for Supper.”

Right about now, you may be feeling peckish. But you may also be wondering: What in the world is a woggin?

New species are discovered all the time.

Unknown old species—extinct ones, found as fossils and then plugged

into our historical understanding of the world—turn up a lot, too. But

every once in a while, all we have to go on is a word. New or old, known or unknown, no one knew what a woggin was until Judith Lund, whaling historian, decided to find out.

Like all professionals, 18th-century

whalers had their share of strange jargon. A “blanket” was a massive

sheet of blubber. “Gurry” was the sludge of oil and guts that covered

the deck after a kill, and a “gooney” was an albatross. Modern-day

whaling historians depend on their knowledge of these terms to decode

ship’s logs—vital for understanding the sailors’ day-to-day experiences,

as well as gleaning overall trends. Being elbow-deep in whaleman slang

is just part of the job.

So when Lund ran into a word she didn’t

know, it caught her eye. Lund was at the New Bedford Whaling Museum,

trying to dig up some data on oil harvest rates. “I was reading a

logbook and charging along beautifully,” she says, “when I came across

the fact that whalemen on that voyage were eating woggins and swile.”

Lund had heard of swile—it’s whaler slang for “seals”—

but woggins were new. She asked the museum librarian, who didn’t know

either. “The woggin was a mystery to both of us,” she says. So Lund did

what any curious person would—started emailing everyone she could think

of, asking if they had ever heard of it.

One of these people was Paul O’Pecko, the Vice President of Collections and Research at Mystic Seaport.

“You know how once somebody mentions something to you, the piece of

information seems to jump off the page when you are not even looking?”

he asks. This quickly happened with woggins. As soon as Lund’s network

was alerted, more mentions from ship’s logs began flooding in. A Sag

Harbor vessel sailing in 1806 “kild one woglin at 10 am.” New Bedford

sailors from 1838 describe “wogings in vast numbers & noisy with

their shril sharp shreaking or howling in the dead hours of the night.”

In a 1798 diary entry, Christopher Almy of New Bedford writes of “one

sort the whalemen call woggins,” which have stubby wings. When they move

over the rocks, he says, they “look like small boys a walking.”

When Lund’s inquiry hit O’Pecko’s desk,

something splashed out of his memory, too. Years before, in his own

research, he had come across the story of Jack Woggin, a beloved ship’s

pet. He dug up the account from an 1832 whaling magazine,

and sent it along. “A person looking overboard saw a Penguin (Genus

aptenodytes), commonly called by the sailors a ‘woggin,’” writes the

author, explaining how Jack got on board. Here, finally, was the smoking

gun: a woggin is a penguin.

But the mystery was only half solved.

Penguins, as we understand them, live in the Southern Hemisphere. And

yet sailors in the north were also getting in on the action, reporting

that they had “caught 10 wogens” or “saw wargins.” “Whalemen were

noticing them before they went far enough south to see true penguins,”

says Lund.

At this point, it was Storrs Olson’s turn

to snap into focus. Olson, an ornithologist with the Smithsonian

Institution, had been added to the email chain early on, but the mystery

hadn’t gripped him. “It was something sailors ate, and they would eat

almost anything,” he says. “I did not pay a lot of attention at first.”

But when it became clear that woggins

were in the north, too, an intriguing suspect loomed: what if they were

great auks? Also flightless, with large, hooked beaks and white

eyespots, great auks went extinct sometime in the mid-1800s, hunted to

death for their oily meat and fluffy down. (Arctic sailors also burned them

for warmth, as there was often no wood where they were exploring.) As

such, we know very little about them, and they have achieved

near-mythical status among ornithologists, who grasp at every scrap of

evidence about how they lived.

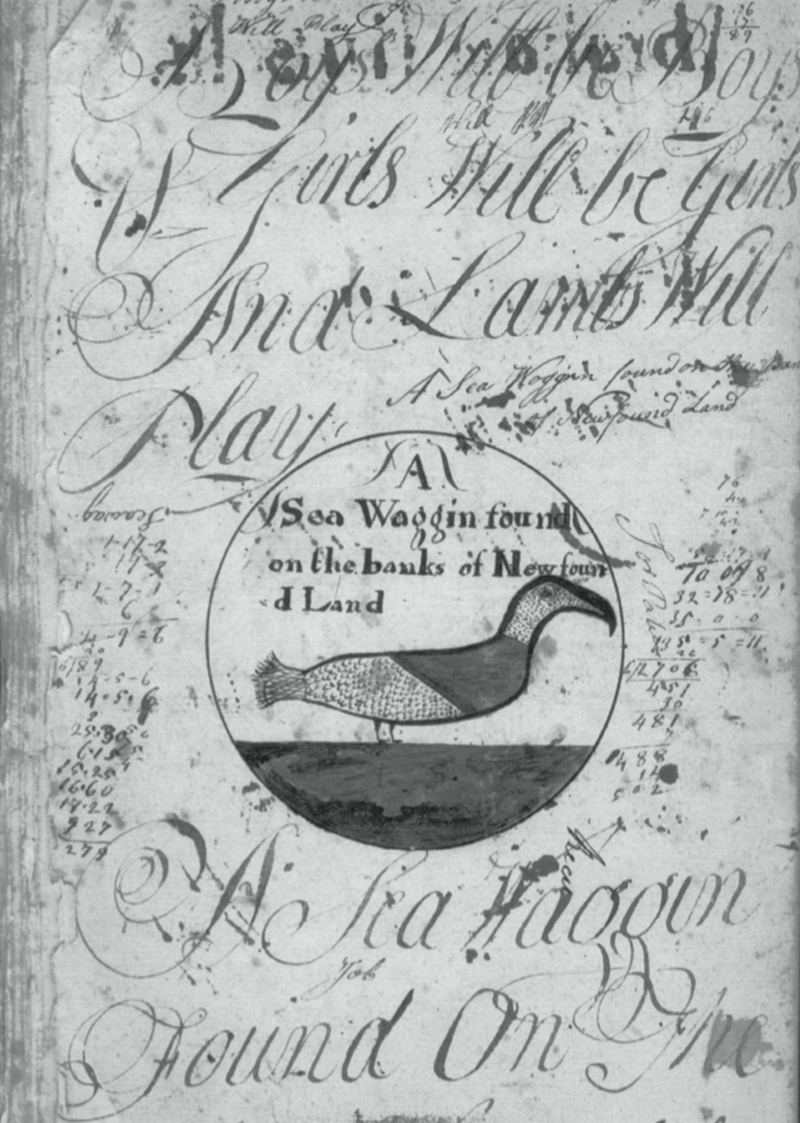

Michael Dyer, another librarian from New

Bedford, had found another major clue: the notebook of a schoolboy named

Abraham Russell, decorated with a careful sketch of a “Sea Waggin found

on the banks of Newfound Land.” The drawing looked as though it had

been traced from a particular illustration of a great auk found in a

popular navigational guide. Further finds reinforced this theory, and

finally, the group of detectives nailed it down: A southern woggin is a

penguin. A northern woggin was a great auk.

Lund and Olson released their first woggin exposé in 2007, in Archives of Natural History. A follow-up was published this month.

(The new paper is a true rollercoaster—early on in the list of woggin

cameos, an explorer from 1860 reports that the birds “excited my wonder

and attention.” Mere lines later, sealers from 1869 are showing off “a

bag full of woggins’ hearts, which we can roast on sticks, and who

doubts that we shall make a heart-y supper?”)

“Our paper was received with considerable interest by the editors of the Oxford English Dictionary and the Dictionary of American Regional English,” it points out, suggesting that woggins may soon officially march into the historical lexicon.

Until then, Olson is using the woggins to

learn more about great auks—he has already expanded their probable

springtime range down to the coast of North Carolina, based on a

sighting from 1762. And Lund keeps the word in her back pocket, a new

species of diverting vocabulary. “I run across it occasionally, and it’s

amusing and interesting” she says. “The woggins live again.”

Now you know!

:o)

Very interesting. New learning for me today. Thank you, Ms coopfeathers.

ReplyDeleteYou are very welcome, Caddie! Glad you like unusual stuff, too! :o)

DeleteInteresting read! I can;t imagine what a woggin would taste like....

ReplyDeleteProbably like chicken - LOL! :o)

Delete