Lifecycle

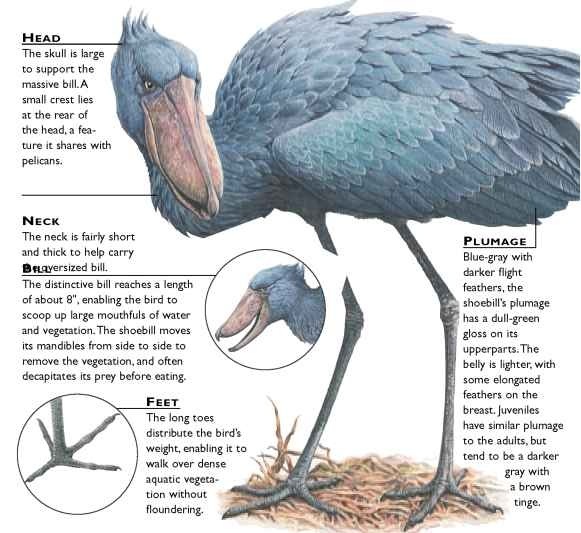

Although given to nesting in remote spots, the shoebill is one of the

most distinctive birds of African wetlands. Its mighty bill is a

specialized weapon for hunting in the water.

Habitat

In northeastern Africa, the shoebill frequents the Sudd, a 52,000-sq.

mile swamp. The bird is most often seen in flooded regions where the

deep, sluggish waters carry large quantities of fish toward the great

lakes of Victoria and Tanganyika.

In Uganda, the shoebill is found on marshy lake margins thick with

reeds, papyrus and grasses. The bird uses this vegetation for nesting

material and to conceal its vast shadow from the fish below. It is often

most numerous in areas where the water has a low oxygen level —

lungfish, a favorite food, then must surface more often, making the

shoebill’s foraging a lot easier

Waterbird

The shoebill is found in marshes and swamps.

• The shoebill follows the sitatunga, an aquatic antelope; it stirs up lungfish, the bird’s favorite food, as it walks.

• The shoebill shares with the storks the habit of defecating on its legs on hot days. This creates cooling by evaporation.

Food & hunting

Fish dominate the shoebill’s diet; it also hunts frogs, lizards,

turtles and snakes, as well as the odd waterbird or young crocodile.

Feeding starts by late morning. Shoebills may fish near each other, but

do not hunt communally. Their method is spectacular but often

unsuccessful, obliging the bird to move a few yards and try again.

conservation

The IUCN (World Conservation Union) has declared the shoebill a

species of special concern because of its restricted range in Africa and

poorly understood biology. The population is thought to be about

11,000, with roughly half occurring in the Sudd.This region is being

drained, along with other wetlands, to create land for crop production.

Cattle farmers are burning marshes, using the land for their stock.

Fishermen disturb the bird during its breeding season, and juveniles are

illegally collected for zoos.

Breeding

The shoebill adapts its breeding behavior to suit the movements of

floodwaters. By mating in the dry season, the shoebill ensures its young

a supply of lungfish, which are trapped in dwindling pools.

The shoebill lays two or three chalky-white eggs on a bulky mound of

aquatic plants trampled on floating marshy vegetation. The breeding pair

continually adds fresh plant material to the nest, which may become so

heavy that it sinks slowly into the marsh. Although breeding pairs may

nest close to one another they never form a social colony.

The parents dutifully tend their silvery-gray, downy hatchlings,

supplying them with prechewed fish and dousing them with billfulls of

cooling water on hot days. The chicks learn to handle fish and eat them

head first. Each juvenile leaves the nest at 13 weeks, but still cannot

fly and relies on its parents for another few weeks. Normally only one

juvenile fledges from each brood.

Job share

Both parents incubate the eggs and rear the young.

fitting the bill

Search…

When the shoebill hunts, it uses various tactics: periods spent standing motionless alternate with a stealthy stalk.

Target…

The bird attacks a catfish in a stand of reeds, toppling forward as it thrusts out its bill.

Control…

The messy hunter skillfully empties water and plant matter from its bill while keeping a firm grip on the prize.

Swallow

After a successful strike, the shoebill takes a drink and then moves to another undisturbed site.

Behavior

The shoebill has a solitary, sedentary nature. Even breeding pairs

seldom feed alongside each other; each one’s territory may extend a few

miles.

The shoebill is sometimes forced by droughts to seek new food sources.

This heavy bird is, however, a reluctant flier because it depends on

thermals (warm air currents) on which to soar: In flight it-draws its

neck back, pelican-style, to bring the mighty bill closer to the body’s

center of gravity. Usually quiet, the bird defends its nest with vigor,

clapping its bill loudly and even leaping onto the back of an intruding

shoebill.

Profile

Shoebill

With stiltlike legs and splayed feet, the shoebill can wade in

shallow water, or stand on floating vegetation, ready to strike with its

extraordinary bill.

Creature comparisons

At 20″ long, the hamerkop (Scopus umbretta) is dwarfed by the

shoebill. It has pale-brown plumage, and the back of its head sports a

crest that gives rise to its name, an Afrikaans word meaning

“hammerhead.” Like-the shoebill, the hamerkop is a waterbird. Its

slender bill enables it to trap a varied diet from frogs to fish and

small invertebrates.The hamerkop’s bill has a tiny hook at the tip of

the upper mandible, helping it pick up smaller victims and rinse them in

water before eating. Although much smaller than the shoebill, the

hamerkop builds one of the world’s largest nests, creating a structure

with an average depth of 5′ and weighing up to 100 times more than the

bird. Hamerkop

| VITAL STATISTICS |

| Weight |

11-13 lbs. |

| Length |

Up to 4′ |

| Wingspan |

6.5′ |

| Sexual Maturity |

3-4 years |

| Breeding .. Season |

October-June |

| Number of Eggs |

1-3,

usually 2 |

| Incubation Period |

30 days |

| Fledging Period |

95-105 days |

| Breeding Interval |

1 year |

| Typical Diet |

Fish, frogs, water snakes, turtles |

| Lifespan |

Up to 35

years in captivity |

RELATED SPECIES

• The shoebill is the sole member of its genus, ‘ Balaeniceps, and

the only species in its family, the Balaenicipitidae. Although DNA

analysis shows it to be related to pelicans, it has been thought to be

most closely related to storks and herons. With its long legs and neck,

it resembles a bulky stork but, unlike storks or herons, it seldom

perches in trees, and nests on the ground.’ |

That is one big boid. Interesting....

ReplyDeleteLook how big they are: https://youtu.be/_4qiM8fn-qw

DeleteReminds me of a preacher we used to have.

ReplyDeleteI hope he gave good sermons so everyone forgot that he looked like a bird!

DeleteWednesday is bird night. Noted.

ReplyDeleteHmmmmmm, not a bad idea, BW!

Delete